For Alana.

Introduction

I’m forgoing a catchy title hoping that perhaps somebody might actually find this blog through a search, as I had to figure this out for myself and it seems the information should be out there.

Right now, there is a lot of discussion about grids for web design. People have finally figured out how to make fluid grids which resize to the form factor (desktop, cell phone, tablet) and maintain the beauty of the original design. There is great content on that, and I cannot add to it. (See References section, below.) But, ironically, with the increased ease of self-publishing, I found it really difficult to find information on constructing a print grid. There are tons of ways to layout grids, but mostly people show you beautiful grids without really explaining how to do them (particularly disappointed with Mark Boulton’s “and then magic happens” approach in his tutorial, which I was not able to genericize). And the ones I did find didn’t suit the purpose at hand. Even many of the designers I talked to didn’t know how to do this. So that is what this article is about. One way to lay out a rational grid mathematically to get a complete design. If you want to layout a beautiful book that suits your content, follow along.

This is not hard. It took me less than 2 hours to figure out the method, it tool longer to write the blog as a tutorial for my designer.

Why is this Relevant to this Blog?

Because this blog is about writing/photography/art and as a writer/photographer/artist, you may very well want to publish your work. As I went down this road for a project I’m working on, there were some missing pieces. I’m hoping to fill those pieces in for those who travel that same road. This method is very specific to photography books.

The Project

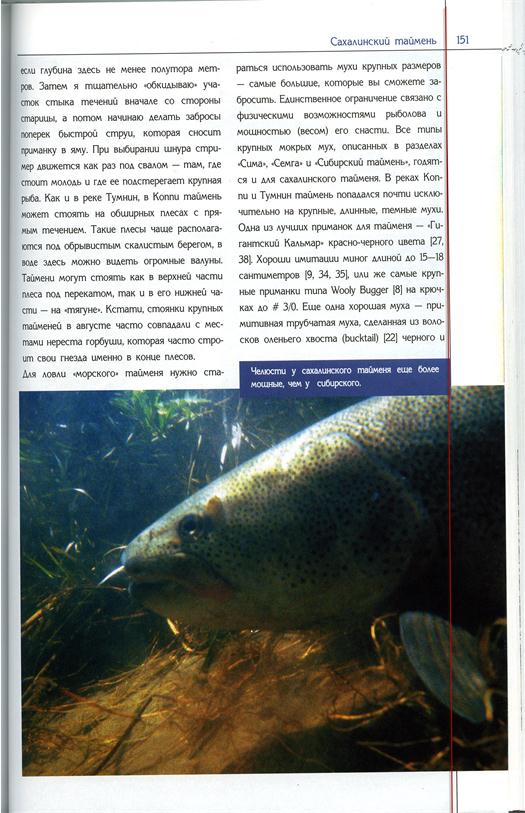

A few years ago, I was fortunate enough to edit Fly Fishing in Patagonia, A Trout Bum’s Guide to Argentina. This was a very impressive book by a couple of young trout bums, Barrett Mattison and Evan Jones, following along in the footsteps of my once roommate, Ryan Davey who made the movie, Trout Bum Diaries, also about that region. I was glad to be able to add to that project, although the book was so well-written originally that my efforts were mostly polishing the chrome. As a result of that book, Ryan “introduced” me to Mikhail Skopets, a Russian fisheries biologist who has spent the last 35 years exploring the Russian Far East. His job is to go to these remote rivers and determine which species of fish live in them. His method is to use a fly rod. In his 30+ years fishing herehe has discovered 4 species of fish, and if you read carefully between the lines realize his first ever taimen on a fly rod was 138cm!

When I say “remote,” I mean remote. I find it interesting that despite our country’s obsession with the USSR as our mortal enemies throughout most of my youth, how poorly educated most of us are about the ex-Soviet states, Russia, etc. For instance, I’ve never seen an English map of Russia that doesn’t label the entire eastern 2/3 of the country as “Siberia,” yet for most Russians, Siberia ends roughly around Lena river the easternmost third of the country above Manchuria and bordering on Alaska, Japan, and N. Korea, is considered the Russian Far East. Like many things Russian, it’s not clear cut and the definition depends on the historical context. Also, because it’s kind of smooshed up on most maps, it’s hard to understand the vastness of this region. There is one island, Bolshtoi, there the size of Michigan that has a population of five. Siberian tigers roam here and eat grizzly bears. Transport is often through ex-military helicopters and tank-like vehicles. It is, perhaps, the last frontier, a holy place for fishermen to at least dream of remaining stocks of 30″ rainbows; two-meter taimen (salmonoids which eat chum salmon whole); every species of Pacific salmon, including the Cherry salmon which we do not have on our side of the pond; Atlantic salmon; and perhaps fish undreamed of and yet uncaught, as Mikhail has already proven.

And yet, as Mikhail so eloquently states, even these remote fish are endangered through over fishing, poaching, and poor environmental practices. Populations are endangered even as they are being cataloged. This, ironically, is one of the values of fly-fishing literature: to “expose” these regions may actually save them. Fly fishermen have a long history of conservation, and tourism may bring enough money to out-compete illegal, immoral, and outdated practices. I hope. Through this project, I have gained a deep respect for Mikhail, what he has accomplished, and the country he so clearly loves. He is humble, he is experienced, and the way he thinks about fishing changed everything about my fishing. One very interesting thing is that everybody I’ve shown the Russian version of the book to has loved it, loved the idea, and is fascinated by it, whether they have ever stood in a river and dreamed of far off places or not.

Self Publishing

One lesson we learned through the Patagonia book is that the authors, who also devoted years of their lives to researching a region the size of California and wrote a fantastic treatise about it, made very little money out of it. There is basically one publisher of fishing books, who has a great network of niche distribution. But the model seems to be more one of constant mass-production and there is little promotion or concept of longevity to keep the book on the shelves. I was, frankly, very disappointed in the publisher’s treatment of the book. In fact, it had already been “edited” when I saw it, yet there were some egregious errors in it. As a result of this, I felt that the high quality and uniqueness of Mikhail’s book would not be well served by going through a publisher. These days, the main reason to do so is only if they are going to do the promotion for you. Since the first version had been self-published and I also have some experience in self-publishing, as well as distributing fly-fishing media through my association with the Trout Bum Diaries, we decided to tackle the project. This means that in addition to editing the book, I also needed to find a designer, and relearn the self-publishing market now that ebooks and print-on-demand have come onto the scene.

Enter the Grid

While we’re at it. Let’s make it beautiful. Do you know what I mean? Have you ever picked up a book and just loved the way it felt as you thumbed through it? You may not even know why, but the combination of size, page thickness, page glossiness, binding, typography, imagery, and layout can make a book beautiful independent of content. Adobe user manuals used to be this way – I just want to rub them all over my body. Books on books are often this way. Even ebooks can be beautiful. It makes no sense to me to publish a book that is not beautiful. It’s like making bad food. Mikhail’s original book was very well done, but we don’t have the files, and there were a few asymptotic things we could do to make it even more beautiful.

Over the years I have been privileged to work with a number of talented graphic artists, whether through designing posters, or web pages, or books. And yet, one thing that they have all had in common is that none of them were taught grid design. That’s like getting a degree in music without learning scales. To the trained eye grids are visible every where from the Parthenon to the Book of Kells. Lot’s of people have written lots of things about the subject, I’m not going to explain why grids are good or why you should use always them, like a bluesman always uses the same three chords. (See References, below.) I’m assuming you understand the why, but are still a little mystified on the how, as I was, despite a lot of research. Enough, let’s start this journey

Looking at the Existing Grid

The existing book is laid out on a grid, mostly. There are a few areas where the grid is broken. I understand the trade-offs in design and production, but let’s face it if I’m going to design and publish this book once, well I might want to do it again, and if so I want to have my one piece be my portfolio piece. I’m not saying the original design is a bad book. I ‘m saying it’s a great book that gave us a great starting place. But since we had to redo it, we got a chance to rethink just a few things. This may have more to do with pure mathematical geekiness than aesthetics, I’ll leave that up to you to decide. For me, a couple of hours figuring out the math was worth the effort not only for this project, but to simplify future projects. For example, Mikhail has so many images we would like to also publish a companion coffee table book. After laying out the first book the second will be a snap.

Here is an example of so many things that were done right with the book. They used a very simple five column grid. The typography is gorgeous (even if you can’t read Cyrillic). And they’ve done a pretty good job of aligning vertically (a “vertical rhythym,” more about this later). What we also like about the book is the page thickness, the gloss, and the size. It’s a book that you can sit and read enjoyably, but also it would fit nicely into your backpack for your trip to the Russian Far East. Because really, that is how we want you to feel about his book. It is a beautiful book, as evidenced by all of the people who have thumbed through it and requested English copies even though they don’t fish.

Here we see a few minor nits to pick (besides the fact I couldn’t get a square scan without breaking the spine of the book). The image has bled off of the grid. Now for some people this is not an issue. Certainly you can see how this happened. Mikhail has been shooting images for 20 years in various formats, they are all different sizes and aspect ratios. The designer has to make choices and here the design goes off the grid. Actually, it’s still on the grid, it just spans that fifth, generally empty column. Is that okay? Sure, it’s a design choice. Likewise, the captions overlapping the image and breaking the vertical rhythm. Is that okay? Yes. It’s part of the design. However, in looking at the redesign, we found the dark blue kind of hard to read, and think that in general our text will be in one column (spanning columns 2 – 4 in the original design), with sidebars for fly recipes, etc. So we’ve made (for now, Mikhail will have to endorse it) some different changes.

Building the Rational Grid

There are grids and there are grids. The existing book is on a grid, but it’s not on a rational grid. A rational grid is a grid where everything is mathematically related to each other. Mark Boulton says:

“Ratios are at the core of any well designed grid system. Sometimes those ratios are rational, such as 1:2 or 2:3, others are irrational such as the 1:1.414 (the proportion of A4). This first part is about how to combine those ratios to create simple, balanced grids which in turn will help you create harmonious compositions.”

Stop Being So Rational

(Actually, nobody ever said that to me.)

Why am I so focussed on a rational grid, when I could spend some time with a T-square and layout an attractive grid? Well, because:

- I am a geek.

- I believe that things that are mathematically proportional are intrinsically more attractive.

- Having all of the math based on ratios will instruct the design decisions from beginning to end.

- It will be faster to layout a grid this time and in the future.

- A trial and error grid that is attractive will probably be rational anyway.

- It solves the one problem with the original design.

Finally, the Rational Grid Tutorial

So, I knew for a while that I wanted a rational grid, but where to start? Many books, and other artworks, are laid out on the Golden Mean. I could start there, and there are some tutorials on that. But instinctively, I believed that the book had to be laid out around some immutable building block, the way the dimensions of a brick house are based on the dimensions of a brick, or a wooden house based on the dimensions of a 2×4. (You don’t find many houses built in odd dimensions: 22′, 24′, but rarely 23′. ) The book is rich in photos, yet the existing treatment of them breaks the grid. Therefore, I thought if we based the grid on the aspect ratio of 35mm film (1:1.5, or in whole numbers 2:3, which thankfully most manufacturers also use for their DSLR images) we would have a good basis for a grid. Khoi Vinh, the influential web designer went into great detail on this in his book Ordering Disorder Grid Principles for Web Design, which is where I got the first part of my methodology.

In fact, one of the most famous grid layouts is based on the 2:3 ratio (UPDATE: read this fascinating history of this classic design), I just felt that it wasted too much of the page for our purposes:

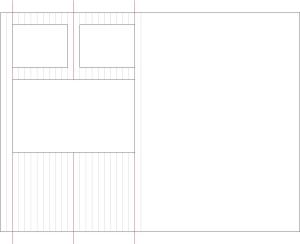

So I broke out some graph paper and a ruler and started counting off blocks that were one and a half times as tall as they were wide. Because I’m designing a book and the space between the pages becomes part of the overall grid, I put two of them edge-edge:

One nice thing about rational designs is that they are well, mathematical. What does this mean to you? It means that the design will be easily divisible into any number of rows and columns.

Start with the Columns

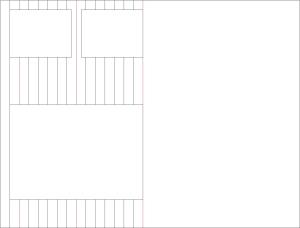

I’ll tell you why in a minute, but for now, we’ll start with the columns to lay out the page. I chose 12 to start with because it breaks down into 2×3, which not coincidentally reduces to 1:1.5.

From there I took off 2 columns on either side for margins, leaving 8 units to work with. I could’ve taken of 1 on each side, leaving 10 units, but this does not divide so easily by 3 or 4 and I was just feeling this out so it seemed less logical.

From there I took off 2 columns on either side for margins, leaving 8 units to work with. I could’ve taken of 1 on each side, leaving 10 units, but this does not divide so easily by 3 or 4 and I was just feeling this out so it seemed less logical.

Now I finally want to add our “immutable block,” the image, so I sketched some 2:3 blocks on the design. Since I know we’ll have both full sized pictures and also half-sized for the sidebars, I put them in here. Note this is the first time height becomes important. But if you measure it out on graph paper as I did you will see that both the height and width of both sized blocks fall on even numbers. Again, this is a direct result of using ratios.

R’uh r’oh. This quickly points out something I nearly forgot. See how the two smaller images abut? We need a column in betwixt like we had on the original design.

In book parlance that is called the “gutter margin.” Here I tried first to use whole units which required 2 to create the distance. This seemed over kill, so I tried 1/2 column x 2, which means realistically I just shifted to a 24 column grid (and the original designer only used 5!)

That looks pretty good to me. We have two units for left, center, and right margins. We have columns of either 9 units (sidebar) or 20 units (full page). Are we done? How should I know, I’m just a arithmetician, not a book designer. However now I have a place to start discussing the design. While I’m at it, though I think I’ll quickly gin up a 16 column grid for the sake of discussion:

Yeah, you got me, it’s actually a 32 column grid because I again split a column to make a gutter margin. In CSS we would just pad this, but in print layout, I need to put it in there.

Have you noticed anything? So far we haven’t talked at all about units, just ratios. I think theoretically, we could layout the whole design in ratios, especially for the web, but as we move to the vertical grid we run into the other immutable building block: font size. Font size is immutable in the sense that once we pick it we won’t change it, all of the vertical dimensions build around it; however, it is mutable in that we have a fairly infinite set of choices to pick from. (In fact, for the fluid grid designs on the web, they are entirely based on the font size in the container. For those who do, and care about, web design, Handcrafted CSS goes into this in great detail. And for web designers there are tools out there to do some of the stuff I’m about to do, probably for print too, but it’s so easy I’ll just show you how I did it.)

Let’s Look at the Numbers

The original book was 8.5″ x 5.75″. Actually it was published in Europe in mm, but I lost my ruler so can’t tell you those dimensions. At any rate that works out to be 1.478260… not quite 1:1.5. Honestly if it was, we probably would’ve just reverse engineered the original grid and moved on. But, as I said we like the size. It feels good in the hand. In U.S dimensions, the closest standard “trim” sizes are 6:x9″ and 5.5″ x 8.25″. 6×9, how cool is that? It’s exactly 1:1.5. Hey, wait, so is 5.5×8.25! The only difference between the two is going to be that the 6×9 math is going to break down very well into whole divisions of the inch and the 5.5×8.25 is not. Honestly, at this time, for electronic publishing (InDesign) I don’t even know how important that is. But it will make for an interesting discussion.

| Intervals | Unit Size per Page Width | |

| 6 | 5.5 | |

| 6 | 1 | .9166 |

| 8 | .75 (3/4) | .6875 |

| 12 | .5 (1/2) | .45833 |

| 16 | .375 (3/8) | .34375 |

| 24 | .25 (1/4) | .22916 |

So, with the 6×9 page you can pretty much do the math in your head. With the 5.5×8.25 page, it’s not so easy, but it’s just a mental paradigm. Once the grid is laid out in the design program it should not really be an issue.

Determining the Vertical Baseline

The reason we need to start talking dimensions for print media when we start talking type is because type is measured in points and points are defined in inches: 72 points/inch. Generally print type is defined in whole points. However, in addition to the height of the type we have the height of the leading or space twixt the lines. Just like bricks plus mortar are used to define modular brick sizes, type plus leading define the line height. Let’s pick a typical font size of 12 pts and a typical leading of 50%, or 6 pts, for a total of 18 pts. Dividing 72 pts per inch/18 pts we get 4. So we know we can get 4 lines of body type plus leading per inch. Now we want our headings to be some multiple of this as well. A 24pt heading 1 plus 50% leading (12pts) would give us 36 pts. So one heading level 1 would equal two lines of body type. This means the type will march nicely down the page (and not overlap like they do on the theme of this blog). And you can do similar tricks for other heading levels to get them to come to whole increments of 18 or whatever you decide your baseline height should be. This is going to be especially important when we have two columns so that the lines will line up aesthetically across columns, as they already do in some cases on the original design. I believe there are tools in book design software to handle most of this for you and help you out.

But there is one thing that I haven’t seen covered: correlating the immutable object and the immutable font. That is: how to we make sure that not only our type lines up, but also that our images and type line up? This is where having a rational grid and not just a bunch of columns really comes to shine. Lets go back to the 24 unit grid. In the 24 unit grid, we know that the large image will span 20 units. If that grid is placed on a 6×9 page where each unit is 1/4″ it will be 20 units x .25″ = 5″ wide, and 13.333 units x .25″ = 3.3333″ tall. Ooh. That looks ugly. Three and one third inches, that’s not the nice even intervals we got when we were looking at the horizontal units! True, but if we convert that to points (3.33″ x 72 pts/in.) we get 240 pts, a nice number. It does not divide cleanly by 18, however. [Aside: Interestingly, if you divide 240, the height of the image in points, by 18, the number of points in the baseline, we come up with 13.3333. Coincidentally our unit height is our baseline height. I have to think if this has any meaning or not.]

However we have two choices on how to handle this.

Either Adjust the Font

The first is to change our baseline height to be an even multiple of our image height. To do this I pick any prime factor calculator using Google. Factoring 240 gives us 2x2x2x2x3x5. From here we know that combinations of these numbers will evenly divide into 240. So we can divide 240 by2,3, 4 (2×2) ,5, 6, 8 (2x2x2), 10 (2×5), 12 (2x2x4), 15 (2×5), 16 (2x2x2x2), 20, 24, 30, 40, 48 (2x2x2x2x3), 96, 120 etc. and get even numbers. A 12 pt font with 50% leading adds up to 18, which is not one of the numbers. But a 10 pt font with 50% is 15 which works, as does 12 pt with 33% leading adding to 15, or 11 pt font with 37% adding to 15. This is what I originally meant but the mutable immutability of fonts. There is the opportunity to iterate here on the typography to get the grid complete. (I played with this in InDesign and you do not have to specify whole point sizes so if you wanted to have an 11.2 pt font with 3.8 pts to get 15, that works just fine.)

Or Adjust the Image

Of course we never set a leading on the image. So if we wanted to stay with an 18 pt baseline then the nearest whole number which 18 factors into is 18×14 = 252, and you would add 12pts, or 2/3 of a line above your image. Or you could go to 270pts and add 1 2/3 lines. This makes sense because one of the issues we had with the original design was the inconsistent treatment of captions. Ideally we would want the image, plus the space above it (leading), plus the caption, plus its leading to be a multiple of the baseline font (e.g. 18) .

And If We Used 5.5 x 8.25

5.5″/24 units = .229″ unit

big image = 4.58″ x 3.055″ = 220px tall (2x2x5x11) (4,10, 11, 20, 22)

8.25″ x 72pts/in = 594 pts/page (2x3x3x3x11) (6, 9, 11, 18, 22, 27,)

These are some weird numbers, fortunately, the page will divide evenly up into baselines of 18, or 22. So it just takes a little math you can still get your vertical rhythm.

UPDATE: Actually, in doing further research these numbers align really well with the traditional scale of 6, 7,9,10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 18, 21, 24, 36, 48…

Don’t Forget the Fiddly Bits

We want to make the smaller images work as well. Remember, because of the gutter margin, these are 9 units wide, or 6 units tall so that is 6x.25″=1.5″ = 108 pts. This does divide evenly by 18 (6), so we match right up. It would be an easy matter to put one baseline above these images.

We can use the same philosophy to make sure our headers, footers and their text and page numbers all align with the grid. The page will be 9″x72pts = 648 points tall. This is 6x the height of the small image and 36 baseline units. Since the over all page ratio is 2:3, and we want the text area to also keep that aspect ratio we can use our dimension of 20 units wide to calculate that the content area must be 30 units tall, maintaining the 2:3 ratio. We can choose to use 3 baseline units for the headers and 3 for the footers, or two for the headers and 3 for the footers with a baseline of room at the top of the content area, or any other combination that works for our design. For instance if all heading 1s start a new page, we may want to incorporate this leading into the h1 dimensions.

Notice that despite calling it a “24 column grid” we are actually only using either 3 or 5 columns, depending on our needs. The grid is no more complicated than the original, we just now have math to lay it out.

One 2-Column Error

When working on the book, we needed a two-column page. Turns out if you use my 2-column solution above, putting 24 columns on a page, then the resulting small image is 2.25 x 1.5. While 6 of these will perfectly fit on the page, this gives an image of 108pt tall, which will not scale evenly against the large size image of 240pt height. The way we solved this was by making the caption for these images 8pt with 4 pt leading, giving a height of 120. Two of these fit into the 240 pt height and our vertical rhythm is maintained.

Summary

- Pick your immutable object.

- Use that aspect ratio as your overall page aspect ratio.

- Play with the horizontal grid to suit your design. In this case an information book that needs both a one and two-column layout.

- Determine your baseline grid to match the vertical height of the immutable object against the immutable height of the fonts.

- Iterate around actual page sizes to fine tune the typography

Conclusion

I’m not a book designer, I’m just a guy who needs to get a job done. Using this method I was able to (re)construct the grid for the book in a logical way, with rules for sizing each of the pieces of content. Will we be able to build out the entire book without breaking the grid? That remains to be seen. But, I hope that this concrete example may help you layout your own book or project. Interestingly, I have never met any of the authors for any of these books, but Barrett is in town and I’m on my way to meet him right now.

Next:

A little more on typography in this blog: Determining a Vertical Rythym for Your Rational Grid

References

http://typophile.com/files/How%20you%20make%20a%20grid.pdf

A basic overview, not really a tutorial

http://whatype.com/texts/the-complex-grid/

This was a good tutorial and a lot of math using the baseline font as the immutable object. Unfortunately, he starts by setting the margins, which breaks the concept of discovering the margins through the ratio and so is not a complete rational grid like I needed.

http://www.thegridsystem.org/2009/templates/indesign-568×792-grid-system-12/

The most complete set of articles, books, tools, templates etc. for grids online.

http://retinart.net/graphic-design/secret-law-of-page-harmony/

A beautiful classic grid layout, unfortunately it didn’t work for the type of book we are designing.

http://www.markboulton.co.uk/journal/comments/five-simple-steps-to-designing-grid-systems-part-1

I read everything Mark Boulton writes. His stuff on grid design is illuminating. Unfortunately this series didn’t quite get me where I needed to be for this project.

http://www.templatelite.com/grid-based-design-articles-tutorials-and-tools/

A bunch of articles on grids to get you started thinking about them.

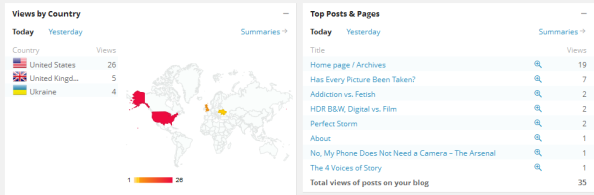

P.S. Who Are You and Where are You From?

WordPress gives me these awesome reports and I can see how people find me, where they live, how they found the blog, what pages they visited. I see people from Europe, Asia, South America, and I always wonder who they are. I would love to get comments from you! Specifically on this post. I put a lot of time into it and I want to know if it is helping you (or overwhelming you).

Elizabeth C Jewell

July 22, 2012

I feel like I’m back in Design class, except most of it actually makes sense ! You are hired ! E

LikeLike

jontobey

July 22, 2012

At least they taught you this in design class. I talked to a graphic artist the other day who didn’t even have to take typography…

LikeLike

Deanna

November 11, 2014

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon everyday.

It will always be helpful to read content from other authors and practice a little something from their sites.

LikeLike

Anomar

August 7, 2020

Found this years later, making some research about how to define a grid for a layout (print or web) – as a graphic designer who mostly did branding, I’m not very good at editorial design – so, I try to get better and understand the design process around :).

Thank you for describing everything so clearly and for sharing your experiences.

(Btw, I’m from Switzerland – as you might wanted to know)

LikeLike

jontobey

August 7, 2020

I’m glad you liked it and thank you so much for the comment! Check out the follow up article: https://gointothelight.wordpress.com/2013/10/13/determining-a-vertical-rhythym-for-your-rational-grid/

LikeLike