Author’s note: This post did everything I hoped, in that it covers a subject I haven’t seen elsewhere; it’s the most popular subject on my blog: despite it’s age it gets regular hits so people must be coming to it from search engines. It took me a long time to come to these realizations and a lot of research for this post. So if you read it, comments are welcome!

Time to get back to some more hardcore photography stuff.

HDR & The Zone System

I was thinking about HDR (high dynamic range) photography the other day. And I realized, HDR is not new. HDR is as old as photography and I use it all the time. We just used to call it the Zone System. In fact, most things we see are in “HDR.”

Let’s start with what dynamic range is. I’m gonna butcher it up a bit here. To be honest, I skimmed a PhD thesis worth of stuff on dynamic range in the last hour or so while contemplating this article. It’s deep and I’m gonna gloss across the top. Dynamic range is essentially how many zones, or f-stops of data your medium (film, digital sensor, Shroud of Turin, whatever) can capture without losing information. In other words, how much contrast can you capture?

Typically, shots that go beyond the range of the camera, or photographer, result in “blocked shadows and blown highlights.” In other words, the shadows are black and the highlights are completely white. On the one hand, this is really easy to do if you don’t understand what your camera is metering on, so you basically under or over-expose some part of the shot. On the other hand, some things just have such a range the camera just cannot capture it.

One of my first blog posts was all about this, I recommend reading it, but I’ll excerpt the part on dynamic range:

Dynamic Range

Okay, what does this mean? Say you are looking at a scene that has both shadows and highlights. Your black dog in front of your snow man, and you have an in camera meter set to spot meter (instead of some broad average, it will become clear why to do this in a bit). You point at the dog and take a picture. Then you point at the snowman, somewhere where the sun is shining on it, and take a picture. (This is where digital is awesome, you can do a similar experiment right now. In fact, you should do this right now, find something with high contrast and take these two pictures.)

Here are two pictures that my friend Kalyx took of the Duvall train station in bright sunlight. In the first she metered on the clapboard, getting good detail on the cracking paint in the light; in the second she metered on the shadow bringing out detail in that paint while the paint in the sunlight is starting to get blown out. These exhibit the typical hallmarks of point-and-shoot photography: blocked shadows and blown highlights.

You Cannot “Fix this in Photoshop”!

This is just bad photography that comes from not understanding the tools. Whether it is a negative or a digital sensor, if you don’t record the information correctly, you cannot ever retrieve it. We’ve had the Zone system for about 100 years, it’s time to learn how to use it!

And, by the way, it shows exactly why HDR came about: because there is such discrepancy in the contrast between the light and dark areas in an image, you have to choose whether you want to capture the shadow details, or the highlights. The camera cannot do both in one capture. (I used to have this problem all the time with my Rottweilers.) In HDR you take the first picture exposing for the shadows, and the second exposing for the highlights and then layer them in your favorite post-processing program for a composite image that has both.

NOTE: Typically people would say you “underexpose, take a ‘correct’ exposure, and over expose.” But what you are really doing is metering on the highlights (since these are brighter you need to close down the f-stop or they will blow out), metering on middle gray (trusting the camera has it figured out), and metering on the shadows to make sure you get the correct detail (opening up the f-stop to let in extra light so they do not come out black). You can choose how much to open or close the lens by how much contrast is in the scene. Generally this is done by using aperture bracketing (f16, f11, f8), which I’ve already suggested should be the default setting on your digital camera. But you can use shutter speed (1 sec, 1/2 sec, 1/4 sec). Heck you could use ASA on a digital camera (400, 200, 100)

Some people take 3 photos 1 f-stop apart, some take 5 photos one f-stop apart. So lets say a digital camera has a dynamic range of 5 f-stops, shutter speeds, or zones. These are all equivalent because each time you open up the aperture by one stop, or double the time the lens is open, you double the amount of light, or change zones by one.

You meter on a scene and it is more than five zones, so you take one picture where the camera meters, one picture by opening up the f-stop by one and one picture by closing it down by one. Now you have covered seven zones in three pictures so you have both the highlights and shadow detail.

(Of course, I’ve been doing similar things on film for years. For instance when we were in Alaska on Prince William sound I was trying to capture the sunset over the ridge across the water. The clouds were luminous, but the backlit islands were blobs. So I set my camera up in the afternoon, metered on the island, took one half of the exposure I metered on (one less f-stop, or in this case 1/2 the time), waited for the sun to light up the sky in the evening, metered, and double exposed the print at one half of the exposure again. This way I had a shot that was both forelit and backlit, the same way you might use fill flash to lower the contrast of a backlit subject. By taking 1/2 of the exposure each time, I made sure that I did not over-expose the film.)

I often also do the same thing with city scenes, taking the image in the daylight while I have plenty of detail, and retaking it at night with the lights on. This way you can get the exposure without the lights in the scene blowing out the image, like at the top of the Needle. (Sorry about the hairy scan.) With film you layer “in-camera,” with digital, it’s post processing. The idea is as old as photography.

Here is an example from fly-fishing guide and photographer Mike Kinney. He does a lot of HDR and was very kind in providing me with examples for this blog.

| Mike Kinney Links |

|---|

| Redbubble |

| Eyefetch |

| Mike Kenney Fly Fishing |

And looking at its histogram. You can clearly see that the bottom of the histogram (Zones 1,2,3) have a lot of information. You can also see that at the upper end Zones 9 and 10 do too, with Zone 10 being “off the chart.” The shadow details were captured quite adequately to the detriment of the highlights in the sky, which are completely blown out.

But in a clear case of previsualization, Mike knew there was more to this scene, which frankly looks pretty pedestrian at the moment. So he took the picture with one stop less exposure to get some of the highlights. In his case he used film speed using f11 and 1/25, 1/50, and 1/100th of a second for the three exposures.

But in a clear case of previsualization, Mike knew there was more to this scene, which frankly looks pretty pedestrian at the moment. So he took the picture with one stop less exposure to get some of the highlights. In his case he used film speed using f11 and 1/25, 1/50, and 1/100th of a second for the three exposures.

And finally, one with the sky metered for its information (1/100s).

Two stops more closed, the sky still has some issues and the foreground shadow detail is nearly gone. So we know that the original shot encompassed at least seven zones, if his camera has a dynamic range of 5 zones. I wouldn’t be happy with any of these images. Yet combined and turned into B&W…

And we have a very supra-natural shot where the strong composition of the image is apparent in a way that never was in color, while the subtle palette converts perfectly. I particularly like the specular effects in the trees. Look how the eye is drawn to the center of the image! This is one of those shots that makes you go “I wish I was there.” But you can’t be “there” because “there” only existed in Mike’s mind. It’s his artistic impression of that time and place that moves you. This is the endearing aspect of B&W, and I want to be very clear about it: the Zone System is all about post processing. Digital workflow is just a new tool for the same old job.

Some people hate HDR, some people love it. For some it’s and end in itself – lurid, for others it’s a tool so subtly applied you don’t know it’s there. In the shot I posted last week that Bernard took of me:

This image is highly post-processed. Not only is it stitched together from several shots to make the panoramic, but he used HDR to balance out the lighting in the stitched images (see Comments, below for more details). Yet this image is not at all unrealistic and does indeed capture the situation the way I remember it. (Minus the big fish I will tell everybody I caught there. ) There is nothing that strikes you as unnatural about this, but this scene couldn’t even have been caught realistically without HDR. So often, the image fails to live up to the memory because we see in HDR.

Hey, Jon, I Thought We Were Going To Talk About B&W Film HDR?

Last week I mused about how my “backup” digital photos from my last Elwha trip, converted incredibly poorly to B&W. I was a little surprised about this. But in thinking about it a little more, I realized a lot of it has to do with my personal style for B&W prints, which is pretty contrasty and would generally exceed five zones of dynamic range.

For instance, just taking Mike’s “straight shot” and converting it to grayscale:

I am unmoved by this shot. No wonder my conversions didn’t move me. When I shoot B&W film, I generally shoot HDR!

That’s because one advantage, the defining advantage, that film still has over digital is that it’s dynamic range is many times greater than digital. If this image was on a negative, I would know I could burn in the sky and bring out detail similar to what Mike did, see below, but a single digital image simply wouldn’t contain the information I needed.

Bruce Barnbaum maintains you can record 18 zones on B&W film (color slide film is about the same as digital). That is 2 to the 13th times more information than a digital sensor that can hold five zones, or about 16,000x the information. In fact analog B&W is so superior to digital, that many photographers shoot film , and then convert them to digital to post-process or print. For instance Nick Brandt, on my blogroll to the right.

Wait just a darn minute, you say. How can you record 18 zones when Zone 10 is pure white? Great question. Paper can only hold ten zones, they eye can perceive more, and B&W film can hold much of what the eye can perceive. It is constantly balancing out a scene. So the trick is to capture all of that information, and then somehow compress the tonal scale to fit on the paper’s scale. This has lead to the famous maxim “Shoot for shadows, develop for highlights.”

HDR B&W Film Example

Let’s take an example. The Zone System basically has three parts:

- Expose correctly

- Develop correctly

- Print correctly

Where “correctly” means to get the image you want or “previsualize.” In a scene with too few or two many zones, you can use chemistry to make the negatives’ overall contrast greater or lesser, and then you have various local controls you can use when you print the image.

I actually took this image to explain the Zone System to my sister who was standing next to me. It is an interesting image, with a lot of problems you might typically find in an image. The sun had just broken over the ridge and was reflecting off of the top of the falls, and there was this cave on the bottom right that was full of flotsam. I had metered on the cave and placed it in Zone 5. That put the white of the falls in Zone 14, a 9 zone difference. When the sun popped out it shown right at the top of the falls, putting it in Zone 18, for a total dynamic range of 13 zones. (Had it shown directly on the falls, I would not have even taken the picture.) In addition to the range, I wanted to make sure that I had definition in the water, not just a big white stripe down the middle of the image, and the wind was blowing. So I needed a pretty fast shutter speed.

I had to make some decisions. I decided I would let the top of the falls blow out and become pure white so that I could get the detail in the cave. I think the exposure was about 1/15th of a second. You can see the branches which overlap the falls are slightly in motion. I can live with these things. This was back before Kodak reformatted their 400ASA TMAX film to have the same grain as the 100ASA. Now I shoot the 400 exclusively to have more options in these situations.

Traditionally, I would’ve shortened my development time to bring the 9-14 zoned highlights in a bit, then used local controls in printing. I still have not had much luck with changing development times and TMAX has so damn much latitude, I’m not sure what I would gain from it. I only even started metering my highlights recently, before I entirely ignored where they landed.

Thinking Negatively to Control Your Contrast

You have to think negatively to understand contrast controls a bit. The whitest parts of the print are the darkest parts of the negative, requiring the longest times under the enlarger. So, the dark cave details pop up right away and will continue to get darker and darker (as they are in the lightest part of the negative allowing more and more light onto the print). The highlights can take 2,3,4, 20x as long to come in. (I have one print where various areas of the print get between 30 seconds and 30 minutes of exposure.)

To help the highlights come in, I pre-exposed the paper to light, so that any additional light would add detail. Then I put my hand over the cave to withhold light (dodged) . Finally I used a piece of paper with a small hole in it to add extra light (burned) just at the top of the falls to reduce the glare area much more than it is in the negative scan here. Because I had previsualized it, I got the final print in just three tries, a major milestone for me. In the final print there is tremendous definition in the water, you can count the logs in the cave, and the big rock center right glows like a ’49 Buick grill.

What if I had done this digitally? Well assuming I could capture 5 zones on my camera, with even the 9 zones I would have to have had my base exposure, one two stops more, and one two stops less. Some people faced with such a range would actually take five, or more, exposures – one for each f-stop. But then the water would not have been frozen, the branches would’ve moved, and I still would not have had any information at the top of the falls to burn it in.

In a master’s hands, like Mike an Bernard, HDR is a great tool in the digital workflow, and maybe even a required one. But in film, HDR is inherent in the image itself. Here is one of my most successful images, a straight scan of a 10 zone image (it has pure blacks and pure whites).

When It Comes to Digital vs Film, It’s Not All Black and White.

It’s the best negative I ever made, and I don’t think I could’ve done it digitally. I’m sorry, but for me, film just kicks ass for B&W HDR and that is the defining reason I still shoot it.

P.S. Who Are You and Where are You From?

This post gets a couple of hits every day. I want to hear from people who read it!

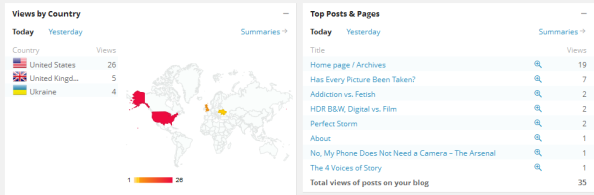

WordPress gives me these awesome reports and I can see how people find me, where they live, how they found the blog, what pages they visited. I see people from Europe, Asia, South America, and I always wonder who they are. I would love to get comments from you!

Elizabeth C Jewell

October 23, 2011

I think I will need to read this a few more times to get the whole thing, or before the test, but I think I already understand the concept, if not the entire B&W technique piece. As always, informative and absorbing. You should be writing a book…

Hugs, E

LikeLike

jontobey

October 23, 2011

As I wrote this I thought I might actually be working towards a book. At least an article. I haven’t seen anybody else taking this tack on the subject.

Actually, this post is all about you! So I hope you can understand it. You were there when I took it, you were there when I printed it. It’s just that it wasn’t until now when I understood it.

LikeLike

Bernard Hymmen

November 1, 2011

Is this post really about HDR? Maybe it’s just a semantic thing, but to me HDR necessarily means combing multiple exposures because no one exposure can capture the entire range of light in the scene. This seems more like a discussion of darkroom techniques to wring the greatest possible information from a single exposure. You run into this kind of limit quickly in the digital realm because you only have 5(ish) stops to work, but I don’t think that makes a 10 or 13 stop B&W film shot HDR because you really haven’t gone beyond the limits of the medium. Adjusting development times, enlarger times, preflashing paper, and dodging and burning in film aren’t really any different than curve tweaks, doing raw exposure adjustments, and creating layer masks in digital. Once you start talking about capturing, say, a 25 stop scene with B&W film, then you’re talking HDR.

To me, the only part of this post that really talks about film HDR is the parenthetical statement above the Kerry Park shot that talks about exposing the film at several different times to slowly build up the whole dynamic range of the scene. That’s a nice trick that you can’t really do with digital, but it does have some of the same hazards like dealing with motion in the scene.

By the way, the real HDR part of my photo of you fishing isn’t recovering the detail in your face and hands. That kind of pseudo HDR because even though I had to blend two separate files for that the detail recovery in the second file came from an exposure tweak in my raw processor for the first file. The real HDR part is the left side of the image with the river, trees, and hillside in the background. That’s where I had to layer a couple of different shots at different exposures to get the full range of light. I think I varied the shots by shutter speed because screwing around with the aperture would have changed my depth of field, thus making it harder to stitch and blend the images in post.

LikeLike

jontobey

November 1, 2011

Thanks for clearing up the details about your exposure. Those are some of the kinds of details I wonder about when I see HDR, and panoramic.

On the rest, this is one case where I totally disagree with you, which probably means I either didn’t make my case, or am not understanding you. Of the several definitions of HDR, I chose “high dynamic range.” When you say “HDR necessarily means combing multiple exposures because no one exposure can capture the entire range of light in the scene,” my point is simply that on the right B&W film I can capture 3x what I can on digital, making several exposures unnecessary. And that, in fact, this is so much a part of B&W that to achieve similar results in digital practically requires you to use HDR. (Since I wrote this, I’ve been introduced to ECN-2 cinematography film which holds similar promise for color, but is so hard to work with, I would choose digital.)

I don’t disagree that ultimately film also has limits, but none of my shots have exceeded it (or needed to, had I done everything correctly). I haven’t gone beyond the limits of the medium, but then I’ve never run into a situation where I needed to shoot more than 15 zones.. Even then, I could flash the film and roll out a few other tricks I didn’t bother to discuss in the already overly long post. But a 25 stop scene? Even most of the HDR articles I read merely attempted to extend from 5 to 7 zones or so. I think i have some film lying around with 12 stops I’m afraid to develop, but a scene with 2^8 more times light than that is hard to fathom.

As far as the things I can do to control the extra contrast in the film beyond what the paper can hold, I also disagree. The techniques of changing development, preflashing the paper, burning, are all to collapse dynamic range of a negative that extends beyond 10 zones to fit on the paper, because that is all the paper can hold. If you’ve blown your highlights in digital, you’ve blown them. There is no recapturing that data. (Likewise, if you don’t have the shadow detail, you are not getting that back by expanding the curve.) Film degrades very nicely in the “blown” highlights, and properly applied they can be recovered and printed. Even without “tricks,” you can take a picture that will span from black to white and cover every zone you can print.

So, my point was that many, most, of the shots I’ve seen done in HDR using multiple exposures, could easily be captured in B&W film in one exposure. Further, if you are taking digital shots and converting them to B&W with disappointing results, as I was doing, the reason is that the medium is simply not as responsive and the shots are not equivalent. A fallacy I was originally laboring under until I thought it through a little.

LikeLike

Bernard Hymmen

November 2, 2011

So this really is a discussion of semantics after all: What is the definition of high dynamic range photography? What test do you apply to know whether you are taking a high dynamic range photograph.

You seem to be saying that there is some absolute number of stops above which you are automatically engaged in high dynamic range photography and that number seems to be somewhere above 5 stops (the stipulated limit of digital cameras). In this view, every photo shot on film that has a range above the magic number is, by definition, a high dynamic range photo. The discussion, however, only gets interesting once one gets near the natural limit of black and white film (say, 10 stops) because that’s when the arcane sorcery of film processing and printing really come into play.

My view of the term high dynamic range is more aligned to a relative understanding of the term than an absolute one. In this view you get into high dynamic range photography whenever the dynamic range of the scene exceeds the dynamic range of the capture device/medium. So, if the scene has a range of 10 stops in it then to record it digitally you need to resort to high dynamic range techniques, to capture it with black and white film you need to resort to…photography. If the scene has more than 18 stops in it (the stipulated Barnbaum limit) then both digital and black and white film are in HDR territory.

LikeLike

jontobey

November 2, 2011

It is definitely semantic. I’m glad you pushed me to define this more crisply. I think you are talking about the process, and I am talking about the product. Remember, this blog, and my musings, are ultimately aimed at the print. Not that every print has to have a long tonal range (i.e. be HDR), but that you innately get that range in film, whereas you have to use a different (but also viable) technique to do so digitally. So I would say for me: HDR is the effect of getting a long tonal range in the final image.

I honestly wish I had said this from your comment: “So, if the scene has a range of 10 stops in it then to record it digitally you need to resort to high dynamic range techniques, to capture it with black and white film you need to resort to…photography.”

It’s all photography, in the end, but the approach is different between film and digital. So if, like me, you are disappointed in your digital B&W compared to shots which may have inspired you, the reason may just be that you need a completely different approach to get those results, and further those results may not always be possible with current digital technology.

Thank you so much for commenting on the blog! I wish more readers took the time to discuss these things and help flesh out these ideas.

When it comes to digital vs film, it’s not all black and white.

LikeLike

paddyacme

July 8, 2017

Wow! I had read an excerpt of this somewhere else and forgot where. I’ve been looking for this for a long time, and just stumbled on to it by looking at something else. Thank you.

I gotta go somewhere in a minute, but I have it bookmarked. I will return to it and give it justice or give it my best.

Thank you

LikeLike

jontobey

July 9, 2017

Wow, people are excerpting me! Cool! Let me know if you remember where.

LikeLike