Image Notes: Two drafts, one of them the actual draft of Michael Kilkenny’s Wake in the notebook I use to record things that make me feel clever. Worth clicking on to see the uncropped version.

Writing Historical Fiction

I recently started serializing a novelette I’m working on, Michael Kilkenny’s Wake. This is probably the scariest story I’ve ever written; not for you, for me. Certainly on some fronts the most ambitious. They say “write what you know.” Well I know a little bit about fly fishing, and I know a little bit about Ireland, but I don’t know much about fly fishing in Ireland, especially in 1937! 1937 equates to the “Golden Age” of fly fishing. I did do enough research to tie the story all together, and may have compressed history just a little, so if you find egregious errors please let me know. At one time I had an annotated copy of the story with references, but I’m not finding it now.

Around this time there was a lot of innovation in Atlantic salmon fly patterns on both sides of the ocean, as well as new techniques developed both in the UK and in America for different species and conditions. The story relies on this to create some tension between the characters. Even in 1937, conservation was a topic, one that still much concerns me and I have not failed to make small mention of it here. Also, without giving too much away, there were changes in Irish House of Lords and heredity in the late 1800s that the story uses, with many of the Great Houses being sold off, and of course the Great Depression was still in force in America, with the Great Recession of 1937 playing a role in the story. Three “Greats” in one sentence, this must be a blockbuster!

The Use of Dialect

Two things especially concern me. The first is that I wrote this in dialect. Well psuedo-dialect. Many people say never to do this, and yet many famous writers do it all the time. The danger is here is great. If, say, you were to write about the American South and wanted to write dialect, you better have a good idea of the state, and perhaps even the county. Likewise, if you are writing about New Yorkers, you better know which borough. In fact, you would use it specifically to contrast your characters. Last I was in Ireland, I was 17, and if you gave me a couple of Guinnesses (Guinni?) I would have an instant brogue, now not so much. Heck, if you asked me to mimic a Vermont or New Hampshire accent (the places where I was born and grew up, respectively), I couldn’t do it. This is compounded by the fact that I was very non-specific about which part of Ireland this takes place in. Of course, you want to write characters and not caricatures, even in a farce, so I relied on a few simple devices rather than try to capture the entirety of the dialect (e.g. “me” for “my” which Liam O’Flattery uses and so I’m okay with it). What I really wanted to capture is the way the Irish can turn a phrase. I still remember my grandmother saying “It’s colder than Greenland’s mountain out there.” And you knew exactly what she meant. Unlike many of the other places in the world where they speak English, even as a second language (I think here of my Russian friend Mikhail and my many Indian coworkers), Americans speak English with neither lyricism nor poetry. Please forgive me as I stretch for this goal.

On a final note on dialect, I will say that as my writing progresses, and I hope it’s progressing, I’ve come more to “see” my stories like little movies in my head. In my head, when this story first told itself to me, it was 1937, and this is how the people talked. If it was a movie, you certainly would expect dialect. I’m going to trust the story to tell itself on this one, until I get an editor.

Irish Currency as a Plot Point

My second concern is, again without giving too much away, is the use of money. British money has always been a bit mysterious to me. Right when the story was written £13 Irish Sterling equaled £12 British. The Irish would go to their own pound the next year, 1938, another good reason to set it in ’37 and avoid further complication. Coupled with that, one pound (also a “quid”) equals 20 shillings equals 240 pence. Then of course there is the farthing, 1/4 of a penny, 1/960th of a pound. I hope I don’t offend my Irish friends when I say that having both multiples of ten and twelve in the same denomination is just a trifle confusing, but shall we say oh, so quaint. (They eventually went to “decimalization” in 1969, about when we went to the Metric System, and I can only hope they were more successful than we were.)

Researching a specific currency at a specific time is non-trivial. I did find that the pound in 1937 converted to today’s Euro would be, roughly £1=€2500, which is also (roughly) how much a week of fly fishing at a manor house would cost you today. But it just doesn’t seem right for it to be only a pound in the story and I doubt the accuracy of the conversion. So I took a different tack. To solve it, I used a trick I used to use bumming around Europe before the Euro came about. We’d get off the train, go to the McDonalds that was guaranteed to be in sight, figure out how much a Big Mac was in local currency compared to dollars (we never once actually ate that crap), and use that ratio to base our valuation of every other thing we bought. So if a Big Mac is 3 clamshells and it’s $1.50 at home, a $1 cup of coffee at home should cost around 2 clamshells. And it turns out there is actually a “Big Mac Index” so we weren’t so stupid! Now I’m creating a Guinness index as the money Michael charges John is the plot hinge for the story. So if a pint is 10d (10 “old pence” before the currency change), how much is a room? Etc. It runs throughout the story. Since a pint of Guinness was 10d then and today runs about $5 here at home, I’m simply scaling up from there.

So if a pint was 10d, then it would work like this.:

240 d/£ ÷ 10d/pint = 24 pints/£.

To use the Guinness Index we would convert that to today’s US dollars like this:

$5/pint x24 pints/£ = $12o (2013)/£ (1937).

One pound from 1937 is worth $120 today, not $2400. Which I’m going to say is good enough for literary work lacking any other direction. So a trip that would cost $2500 today, would be $2500/$120/£ ~21 £. It still seems very low to my eyes, but it’s the very best I can do at the moment. I’m going to think of a pound note as roughly a $100 bill. Again, all corrections to egregious errors much appreciated.

On a side note to this, you may ask, “How did you figure out the price of a pint of Guinness in Ireland in 1937?” Well, I’m glad you did. I emailed Guinness and their archivist had the answer for me in 24 hours. Seriously? How freaking cool is that? Go buy a pint of Guinness simply for having the best customer service of any company I’ve ever heard of.

Being Farcical

There was one last concern, fishing literature is rich with poaching tales. I was first exposed to them in the Fireside Book of Fishing Tales, which I took from my parents’ library and read one summer. This book probably made me a fly fisherman, and a romantic. So, I wanted to write a poaching tale, but it came to me as a farce. Just one problem: I’d never written a farce. Writing funny is hard. Really, really hard, But farces have a certain formula. So I did some research on this, too. Per the dictionary:

a. A light dramatic work in which highly improbable plot situations, exaggerated characters, and often slapstick elements are used for humorous effect.

Wikipedia says:

In theatre, a farce is a comedy that aims at entertaining the audience by means of unlikely, extravagant, and improbable situations, disguise and mistaken identity, verbal humor of varying degrees of sophistication, which may include word play, and a fast-paced plot whose speed usually increases, culminating in an ending which often involves an elaborate chase scene. Farces are often highly incomprehensible plot-wise (due to the large number of plot twists and random events that often occur), but viewers are encouraged not to try to follow the plot in order to avoid becoming confused and overwhelmed. Farce is also characterized by physical humor, the use of deliberate absurdity or nonsense, and broadly stylized performances. Farces have been written for the stage and film. Furthermore, a farce is also often set in one particular location, where all events occur.

Other sources I’ve read say they must include a murder and gender confusion. (Oh, oh, looks like I need a chase scene…Good thing I serialized it!) Many people cite Frasier as having some of the best modern farces, so for two years I have been recording reruns and watching them. Like all of the other issues here, if there is anybody with suggestions for punching it up, I’m all ears. I’m simply not that funny of a guy, at least on purpose, and again my reach may have exceeded my grasp. Rhonda? Spasari? Hoffman? Where are you?

Off to do some math and write a chase scene, thank you very much for reading along.

P.S. Who Are You and Where are You From?

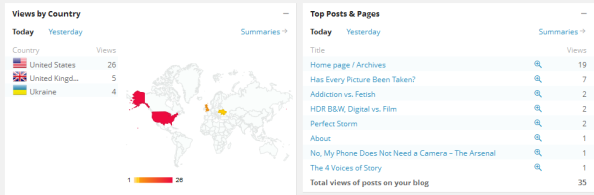

WordPress gives me these awesome reports and I can see how people find me, where they live, how they found the blog, what pages they visited. I see people from Europe, Asia, South America, and I always wonder who they are. I would love to get comments from you! Kind of like a WordPress stamp album.

Elizabeth C Jewell

March 17, 2013

Interesting, really

LikeLike